Darryl Stickel on Building Trust for successful collaboration

Darryl Stickel on Building Trust

I was introduced to Dr. Darryl Stickel by a mutual friend. Darryl was a practicing consultant, academician and author, and has written a fabulous book on the topic of trust, which is near and dear to my heart, but mostly because of the contrarian that I am. And Darryl and I, I think, share, uh, an orientation.

[Darryl] A few things that will help them understand my perspective. One is I was born and raised in a small town in northern British Columbia, Canada. I grew up in a fairly isolated community, which meant that I grew up feeling like it was important for us to help one another.

I went to undergraduate and did a master's degree at the University of Victoria. Then I went to Duke and wrote my doctoral thesis on building trust in hostile environments at the business school there. I left there, went to McKinsey and Company, worked there for a few years, and was injured in a car accident which meant that I couldn't work 80 hours a week anymore. And so I started a small company called Trust Unlimited. I spent probably the last 20 years of my career devoted to helping people better understand what trust is and how it works and how to build it.

You were a very humble guy, but you didn't hesitate to say, “Carlos. I'm one of the world's leading experts on trust.

Well, we don't necessarily have a leaderboard or a scoreboard, but I listen to some of the other folks who are counted as experts, talk about trust, and I get frustrated. I was at a conference held at Duke that was labeled Building Trust in Institutions, and overwhelmingly what they talked about was the lack of trust. There was a real shortage of conversation about how to actually build it, how to make things better. I listen to some of the folks who are counted as experts on trust - and I don't want to offend anyone - the work they're doing is great. But there's little that you come away with thinking, “Okay, I could change my behavior,” or “There's something I could do with that.” There's little of that practical applied piece in a lot of the really great literature and thinking that they're doing about the topic. There's more about, “Yeah, we don't have those things.”

What to do to build trust

I've been involved in this space consulting to teams and their leaders for decades. I think it's fair to say trust is an essential element of any kind of collaborative endeavor. And in fact, there are people who will tell you, you can't have great teamwork without first having great trust. And so there are a lot of products out there, a lot of people trying to solve this trust problem. And a lot of techniques, a lot of tools, a lot of exercises. And I would say millions of dollars a year spent on trust. And then along comes this guy, Darryl, who says, “Wait a minute. I don't think that's all quite right.”

One angle is, of course, people are talking about the absence of trust, not what to do to build it. But look, all this trust building can't be wrong, can it? All this money being spent, all these exercises, all these consultants, Are we that far off base? What do you think?

It's not wrong, it's just not complete.

I'll give you an example. One of the books that was really popular for a bit was a book called The Trusted Advisor. It was a book of lists. It was incredibly thorough. It took almost every social psychological bit of research and theory that we had, and it threw it against the wall. There were, I think, 70 or 80 lists. They averaged about seven or eight items. Per list. So you finish reading that and then you think, well, now what do I do? And when do I use which item? There's not a formula that people can use. There's a series of actions that get proposed.

For those who haven't read the book, can you tell us a little bit about that and maybe give us an example of what one of those lists says?

They would have a list of things around communicating more effectively, and they would talk about transparency. One of the items that really stuck in my mind was, free your mind. And I, I thought, what if it doesn't come back ? But you're looking at hundreds of suggestions.

What’s missing in how we build trust now

When I was working on my doctoral thesis, I was working for the federal government in Canada. They would ask me these deep philosophical questions like, What is self-government? or What will the province look like 50 years after claims are settled? The last question they asked me was, How do we convince a group of people that we've treated horribly for over a hundred years that they should trust? This would be the First Nations folks who are still struggling today.

My first response was. “Maybe it would help if we were trustworthy.” That didn't get nearly the positive response one would hope for from the government. And by mutual agreement I left not long after, but it got me thinking about long term disputes and why they're so resilient.

As you say, there are thousands of people talking about trust. They wrote the book 20 years ago, The Trusted Advisor. Have things gotten better? No, they've gotten dramatically worse. And we still have people talking about it and it's still getting worse. It's at the lowest levels we've ever seen. I may not be the Messiah. I may not be completely right. But I can tell you there's something missing because if we understood this really well, we'd have fixed it by now.

Barriers to trust

What attracted me to your work was that it is, on the one hand, intuitive. But it's also quite detailed. It gives you a process, not just a list of steps, a way to frame trust so that you can then do things about it. As you say, we've never needed it more. Early in the book, you talk about barriers to trust. Talk a little bit about those barriers and what you see them as.

How trustworthy are YOU really?

There are some things that prevent us from actually making progress on this, and I've run into them on a number of occasions and I still run into them. I think the one that's most prevalent is probably the belief held by most of us that we're trustworthy. I think the research suggests that 95% of people believe they're more trustworthy than average. Not only is that statistically impossible, but it creates problems for us because we have this profound lack of awareness about who we trust and how much we trust them. And we don't always identify trust problems as trust problems. But when we do, we assume that, hey, we're good. So, it's somebody else's problem, it's somebody else's fault. So we don't need to do anything about it. It's all on somebody else. That creates a profound barrier to us actually taking steps, proactive, productive steps to being intentional about building stronger relationships, because we assume it's somebody else's fault.

So that's number one. I probably ought to be more circumspect about how trustworthy I am perceived to be.

Part of what I try to do is help close the gap between how much we are trusted and how much we should be. I really try to help people be more effective at communicating how trustworthy they are and when they're trustworthy and getting a more accurate picture of that for themselves. So this is barrier number two, this lack of awareness. You know, I'll ask people, “Who do you trust?” And they'll give me these close, tight, personal relationships: spouse, best friend, sibling, parents. They give me these sort of really tight close relationships. And the reality is we trust people all the time. We just trust some people more than others. Having that awareness that it's not just those close, tight, personal relationships, but that it's a part of the fabric of everyday life.

A good friend of mine who helped with the writing of the book, Mike Wicks, asked me to think about what if we wrote a book about a world where there was no trust? And I started thinking about that. We wouldn't go out in public, we wouldn't go to restaurants. Money would cease to be a currency. Trust is a social lubricant that allows society to function. We've seen research that tells us that economies grow more effectively, companies are more effective, groups are more effective; there's all these things that are positive outcomes of some level of trust. and of being aware and able to build trust.

Vulnerability without predictability

So, when I flip that question, and I say, not who do you trust, but who trusts you? I get these really long pauses. And then some folks will say, “Well, maybe the same folks that I trust,” parents and siblings, and those kinds of things. Leaders, in particular, will say to me, “Well, how do I know? How do I know if somebody trusts me or not?” Which is a good question. And so for me, partly I go back to the definition which is: trust is the willingness to make yourself vulnerable to someone when you can't completely predict how they're gonna behave.

There's elements of uncertainty and vulnerability in that definition. And if I want to know if somebody trusts me, I ask myself, “How can they make themselves vulnerable to me?” And then do they? So, if I'm a leader, do they give me their real development needs? Do they talk about things outside the box? Are they willing to make mistakes? Do they push back against ideas they don't think are gonna work? Do they give me real feedback?

Trust and Psychological Safety

This has some resonance with the work around psychological safety. Do they feel psychologically safe in my presence?

Yeah. When I use the book and when I talk about different elements of the book, I try to be inclusive of great work, like Amy Edmondson's work on psychological safety or Brené Brown's work on vulnerability. Also, Daniel Goleman's work on emotional intelligence, Daniel Kahneman’s work on thinking fast and thinking slow. All of these things are elements that you can bring to the table and say, “Hey, somebody's done really good work on this.”

I overestimate my trustworthiness or trust-ability.

I'm not as aware of how active and present trust always is in situations.

What's number three?

You can improve your own trustworthiness

Three is that often people will believe that trust is what it is, that we can't do anything about it, that it's too complicated. I've had some people ask me, can we actually build trust or can we rebuild trust? Recently, Rachel Botsman, who's the Oxford Professor of Trust, said maybe it's inappropriate to talk about building trust, but instead we should talk about people giving trust, which changes the whole perspective.

I've seen different people talking about trust levels or trying to promote trust by making others more trusting. I hate that. There's some work that was done on the neuroscience of trust that talked about changing people's willingness to trust. That we could introduce chemicals into the brain, that we could create situations that would cause them to be more trusting. Well, we've done hundreds of years of research on that. It's called alcohol. We can make people make decisions that they regret later fairly easily. I am leery of making people more vulnerable than they're comfortable being. I'm more proactive around how do I make myself more trustworthy, and how do I communicate more effectively?

building trust need not take long

That notion of turning it around. It's not about them. It's about making myself more trustworthy as the fulcrum on which this may pivot. Now, the fourth barrier is what?

People often think that while trust matters, it's a long term. And they're evaluated on short term so often, and they think, I don't have the time that I'm fighting all these fires. And what they don't seem to realize is that a lot of the fires they're fighting are underlying symptoms from trust problems. We can actually see fairly quick turnarounds. I have personally worked with leaders who have had profound changes in the response that they receive. In a couple of instances, it was a couple of dads who were struggling with their sons, who within a couple of months have gone from conflictual to closer than they'd ever been. We can make profound change fairly quickly. It's just we need to be thoughtful about it.

Why defining what trust is matters

I think one of the barriers to trust is the many, many, many different understandings of what it is. I was reading an article in Harvard Business just today about why spending too much time on trust can actually bog things down. One of the problems the author cites there is, it's a woolly concept. It's a bit fuzzy. People think they know what it means, but we don't necessarily all sit down and agree what it means. I think that's a barrier too. What do you think?

I absolutely agree. I had the good fortune of doing some work with SAP, huge software company out of Germany. I did leadership workshops with folks virtually from all over the world. They kind of all came back and said, “You know what? This model makes sense. As you said before, it resonates. They've done remarkably well in terms of trust evaluations within SAP. One of the things they find really powerful is having a shared vocabulary. They're all using the same terms. They all have the same definition for what trust is.

I worked with a leader whose trust score was 13 out of a 100. Within three months, their trust score went to 80 out of 100. And really all we did was, I talked to the leader for a bit, but we sat down with their team and said, here's what trust is, and here's how the different levers work. Now, how could this leader pull those levers? And we all got on the same page. Within a couple months it was profoundly different.

The Trust Model

And that's a perfect segue, Darryl, to talking about the model. On one level, it's pretty simple and intuitive. Can we talk about the bases of trust, the fundamental elements of the model?

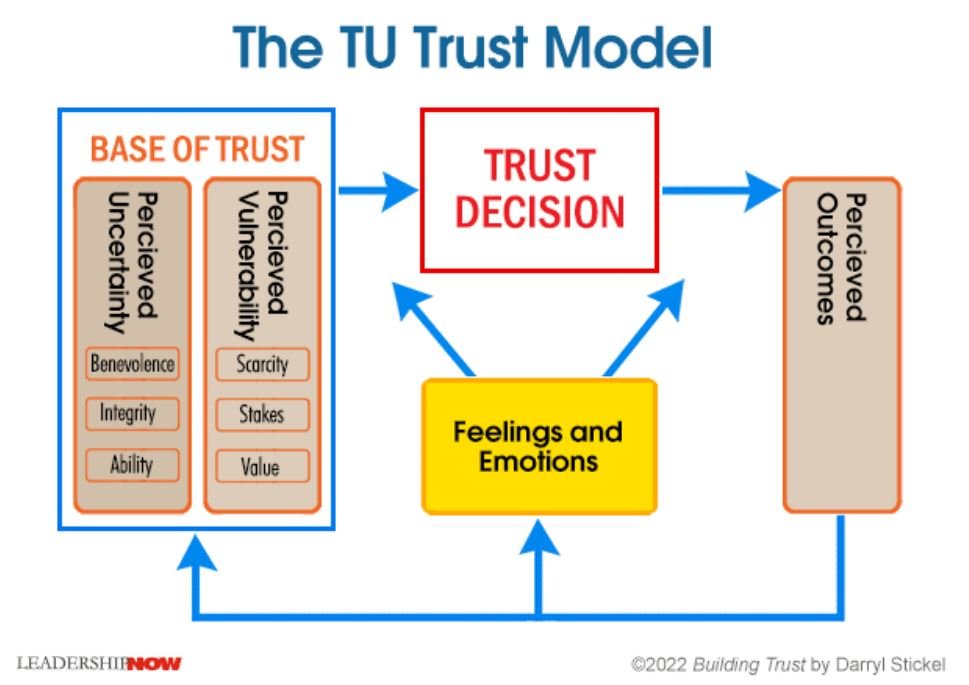

Yeah. I believe that when we're deciding whether to trust someone, we ask ourselves two fundamental questions.

“How likely am I to be harmed,” which is perceived uncertainty.

“If I'm harmed, how bad is it gonna hurt?” which is perceived vulnerability.

Those two things, perceived uncertainty and perceived vulnerability, are the basis of trust and they combine. Uncertainty times vulnerability gives us a level of perceived risk.

Vulnerability and Perceived risk of uncertainty

We each have a threshold of risk that we're comfortable with. It's different for each of us, but through our lives and our history and our experiences, we've developed this tolerance. If our perception of the risk goes beyond that tolerance, we don't. If it's beneath it, then we do. This does a couple of things for us. It allows us to think more broadly about how I build trust. It actually seems fairly simple now because all we have to do is think about

Where does uncertainty comes in?

Where do perceptions of vulnerability come from?

How do we take steps to reduce those to make somebody else more comfortable, to get their risk perception below that threshold?

Now, all of a sudden now we've got tools that we can use and we understand that one approach is not gonna work in every setting, every situation. And we can think about relationships; early in a relationship, uncertainties high. That means the tolerance for vulnerability is low. As that relationship evolves, our uncertainty starts to decline, which means the range of vulnerability starts to expand, that we can accept and still fit.

Trust and Relationships

So, what you're saying there is in a normal working relationship, there is a natural movement towards a greater sense of trust.

Yeah. As we get to know each other.

So. those exercises where people get to know each other, whether it's your Myers Briggs or your DiSC profile, those do move you along the path of trust a bit?

They do a bit. One of the things that I have to be leery of sometimes when I come to give talks is, is people are like, “Oh my God, it's the trust guy. We're gonna walk around blindfolded. We're gonna fall off of things. We're gonna be walking through hot coals.” I don't do any of that. There's no singing, no drum circles, none of that stuff. Not that there's anything wrong with any of those things, but it's not what I do. Sometimes we need to collaborate to build trust, right? The article you were talking about - if we can actually reduce the level of vulnerability in those initial collaborations, they can serve as a mechanism for helping us reduce uncertainty with each other as we go forward.

If the stakes aren't too high right off the bat, then they can actually serve the function of building trust as we go. There are multiple ways we can reduce uncertainty. In fact, one of the “Aha!” moments I had when I was working on my thesis the realization that overwhelmingly the research is focused on uncertainty…

And not vulnerability. Is that your point?

It talks almost not at all about vulnerability, which means that we can't talk about depth of relationship. We trust some people more than others, and I say that and everyone goes well, “Duh. Like, how did this guy get a PhD?” But the literature doesn't treat it that way. It treats trust like it's a dichotomous variable. Like it's either there or it isn't. Like an old light switch either on or off. The reality is that you and I can trust each other in some settings and maybe not in others.

Trust and context

Trust exists in context. I'm interested in that because so many people out there are pedaling their wares. “Let's go off into the woods and do paintball or do rock wall climbing because you and I have got a project that's due at the end of the month. You haven't come through with the stuff you're supposed to do.” But, just because we did a rock wall together, it doesn't mean I'm gonna trust you're going to deliver. Context is different.

Context really matters, and it's one of the things I discovered. I was working with the Canadian military trying to help them figure out how to build trust with the locals in Afghanistan. The reality is, is that one guy in a military uniform with a machine gun looks a lot like another guy with a military uniform in a machine gun. Those individual elements is where 95 to 99% of the research is. Uncertainty comes from two places. It comes from us as individuals, and it comes from the context. Early on the context bears much heavier weight when we're evaluating. Talking about the context helps us explain why we could trust some people immediately or mistrust somebody immediately without knowing anything about them as an individual. And over time the weight of those things, the individual traits and the context start to shift as we get to know somebody better.

The context is a powerful influencer. The example I like to use is the doctor's office. We go into a doctor's office. we're sitting there, somebody walks in with a white coat on and a stethoscope around their neck and they say, “Take off your clothes.” And we do. That doesn't work in other places even if it's the same person, right? If we were to go from that doctor's office to a washroom at a gas station and have the same two individuals and you're leaning against the counter and some guy comes in with a white coat and says, take off your clothes, it goes from credible to creepy and a heartbeat.

Pulling the levers of trust

In part, I think of building trust as using levers. We all have the ability to build trust. Some are just better than others at it. Those who aren't very good have a lever that they pull and they pull it over and over and over again and just hope it lines up. Those who are better have multiple levers and those who are really good have multiple levers and they know when to pull which one.

What I do with the training that we do and the workshops and the book is I try to introduce people to multiple levers. Then I talk to them about how we pull each of those levers more successfully. Then we start to try to help them diagnose: Okay, where's the gap here?

You've got this model that basically has perceived risk, perceived vulnerability within a context that yields how willing I am to take the risk trust, right? That's the basic equation?

Uncertainty times vulnerability gives us a level of perceived risk. And our uncertainty is coming from a couple of places. From us as individuals and from context, and we can take steps to reduce those. Our perceived vulnerability comes from how we value the stakes, what we think is at stake. Then we've got our risk preference, which is based on our history. The stuff that talks about making us more trusting is talking about trying to move that threshold of risk that we're comfortable with.

I want people to go buy your book. What's the title of the book, Darryl?

It's called “Building Trust: Exceptional Leadership in an Uncertain World.”

You say that it's about me becoming more trustworthy. It's not about building trust in some space between us. It's about me saying, “I'm gonna take responsibility for understanding how trustworthy I am,” and then pulling these levers move the needle on that. Is that accurate?

Yeah. It's to make your perceptions of me more accurate. It's trying to communicate more intentionally, more clearly. And one of the struggles we run into is that people will say, “I do all those things. I do those things to reduce uncertainty.” And the question is, “Says who?” If I tell you I'm trustworthy, that's nice, but you actually have to believe it. So, the onus is on me to help you understand that.

Got it. So, what you're doing is you're giving leaders, and I would imagine team members, anybody at any level, 10 levers, all of which you say you can have some influence over and therefore can affect how trustable or trustworthy you are.

Right. It's giving people control over their own success. It's one of the few factors we actually have direct control over. The more senior we become or the more complex our team becomes, the less direct control we have over outcomes. And the more dependent we are on other people, the more important our people skills become for us to be successful.

So, if I wanted to evaluate my trust capability, I would have other people fill out a survey that gives me feedback on those 10 levers.

Absolutely. And in the book, I try to lay out approaches you can take to pull the benevolence lever. Here's some things you can do to pull the integrity lever. Here's some things you can do to pull the ability lever. Those are sort of the three levers within us as individuals. Here's how you pull the context lever to make your context clearer or to constrain yourself within the context to make it easier to predict you.

It's very pragmatic. Here's the language we can share around trust. Here are 10 areas where you can work to shift levels of trust in yourself. Ultimately, if you and I both work on our levels of trustworthiness it ends up

A success story and its profound impact

One of my favorites: I teach in the Luxembourg School of Business in the MBA program. One of the tasks I have them do is apply the model to their own. They pick a relationship in their life that they're gonna take and apply the model to. I had a student, great guy, and he had been away working in Brazil. His kids were three and five and he had missed most of their lives growing up. He said, “I think this relationship is broken forever. I'm terrified. I don't know what to do. I react badly. They're scared of me.” Through the course of my class, he got some insight about the model. We had some conversations. I had some emails back and forth with him. After three months in his final assignment, he said, “Things have turned around completely. My children run to me. They fight over who gets to sit next to me at dinner. They fight over who gets to have me read stories to them at night. The whole thing is completely changed.” I get experiences like that often where I see profound behavior change.

The struggle I have, Carlos, is that I'm dropping grains of sand in the ocean. I would love it if you and your brilliant listeners would help me pick up some very big rocks to make waves to help us, because that's the mission I'm on, is to help us all get better at building trust.

We will certainly reach out to all our networks and get people talking about this. I think we can start a wave. What you're doing is vital and I can't wait to work with you on something. I'm looking forward to a partnership.

That'll be fantastic. I would absolutely love that.

Run, don't walk to your computer. Click on the links, take a look at Darryl's book, BUILDING TRUST, his blog and his work, and spread the word. I look forward to being with you all next time on the next episode of Teaming with Ideas.

Darryl Stickel holds a PhD in Business from Duke University and wrote his doctoral thesis on building trust in hostile environments. After working at Mckinsey & Company as a consultant Darryl founded Trust Unlimited. Through his company he has worked with a broad range of organizations and individuals helping them understand what trust is, how it works, and how to build it. Darryl’s clients have included financial services, telecoms, tech, families, and the Canadian Military in its attempts to build trust with the locals in Afghanistan. Darryl has also spoken at some of the world’s leading academic institutions and regularly exchanges thoughts and ideas with other leading scholars.

Dr. Stickel has a rare blend of deep theoretical knowledge and practical applied experience. The experiences of working with clients on a broad range of topics have provided a remarkable learning experience which allows him to approach new settings with confidence and compassion.

Darryl’s position at the Luxembourg School of Business combined with his ongoing work with global clients has allowed him to apply his model across a broad range of cultures and settings. Consistently the response of participants is that the model used makes sense and allows people to make behavioural changes that have profound impacts on their relationships.

Darryl’s book Building Trust: Exceptional leadership in an uncertain world was released in June, 2022. The book is a practical and applied guide based on his 20+ years of helping people solve trust-based problems. Trust Unlimited has also developed a set of virtual offerings intended to help people better apply the model to their lives. This virtual approach includes multiple learning modalities and represents a significant evolution of the training approach. Early responses from senior leaders have been extremely positive.

To see what clients are saying please refer to the client testimonials.

Darryl suffered a mild traumatic brain injury in 2001 and has lived with chronic pain since that time. Darryl has had to work with treatment teams over the last 20 years to cope with and overcome the ongoing challenges posed by his injuries.